This true story focuses on what may be the first act of ‘Reconciliation’ in Australian history. The heroism exhibited by two Aboriginal tribesmen, Yarri and Jacky Jacky, in a bid to save the lives of many flood bound white settlers, is legendary. Their courage pushed the boundaries of human endeavour by any standards.

The first township of Gundagai sprang up around the short stretch of Murrumbidgee River where it was possible to cross in safety for many miles in either direction. During periods of low river flows, bullock teams and horse drawn wagons were able to carry settlers and their possessions across the river here, at ‘the crossing’, as they headed southward in search of new lands.

It was logical, therefore, for businesses to start up around ‘the crossing’, in order to service the ever-increasing number of travellers who were passing through. At first, tents were pitched and later as commerce thrived more substantial buildings were erected along the river flats and banks. The township was also surrounded by a branch of the Murrumbidgee known as Morley’s Creek on the northern boundary of the floodplain.

Sometimes travellers had to hold up for days at a time waiting for periodic flood events to subside, in order for them to be able to cross the river in safety. These floods were of relatively minor significance. Each time the water would peak to a height of about one and one half feet (0.5 metres) inside the buildings. The residents became used to taking refuge in the lofts which had been designed for this purpose. Inns and hotels conducted a roaring trade accommodating guests who were temporarily unable to leave town. Doctors, dentists, shopkeepers, merchants, blacksmiths, saddlers, wheelwrights, carpenters, barbers, horse breakers, and labourers were all in constant demand for work.

The white settlers refused to heed the dire warnings of the local aborigines who told them to relocate their buildings to higher ground on the hills surrounding the river. The tribes were adamant that the ‘Mother of All Floods’ would eventually wash the whole town away, taking all with it. With 10, 000 years of local knowledge, the aborigines knew that the township was built on a floodplain and that it was only a matter of time before a catastrophe occurred.

By 1852 Gundagai had a white population of 250 people. There were residential buildings as well as shops, public buildings, a police station with a lock-up, banks, hotels, a school house, a flour mill and even a punt to ferry passengers and their wagons and carts across the river. However in June 1852 it rained for nearly three weeks non-stop. On Thursday morning, June 24, Gundagai was completely isolated as both Murrumbidgee River and Morley’s Creek were swollen with rising flood waters. By later afternoon of the same day most of the floodplain containing the township was under water. When the rain stopped, people thought the worst was over unaware that the full force of the floodwater in the upper catchment area was yet to hit the town. They were complacent enough to reject offers by the punt-owner to ferry them to the safety of the higher ground on the southern side of the river.

On Thursday night the water flowed through the houses at heights of about six and one half feet (2 metres), which had never before been experienced by the townsfolk. On Friday morning, June 25, people were climbing out of their lofts and on to the rooftops. Several drowned in the process. Logs and debris from upstream were cascading down the river at frightening speeds crashing into houses. The punt crashed into a tree whilst attempting to rescue victims and was destroyed, killing all but one aboard. For all attempts it was now too dangerous for rowboats to be of any use at all.

That day the lone figure of full-blood aborigine name Yarri, crouching down on his knees on the bottom of his frail bark canoe, headed out into the flooded Murrumbidgee which was by now two thirds of a mile wide (1 km). His canoe could only hold himself and one other. Again and again, Yarri forced his way across the raging torrent. Without the courage and superb skill of Yarri, the canoe would have been smashed to pieces or sunk. One by one, he rescued flood victims and brought them to land. As darkness closed in people were forced to cling the highest rooftops and chimneys or swim to the nearest treetops still above the water. By Friday night the river was rapidly rising at the rate of over three feet (1 metre) an hour. Many families were separated never to be reunited again. With soaked clothing many succumbed to hypothermia and frost bite due to the freezing cold winter temperatures.

In the early hours of Saturday June 26, the river peaked at about twenty feet (6 metres) and had swollen to a width of one mile (1.6km). Guided only by the cries for help and the moonlight, Yarri continued to fight his way through the ferocious waters skilfully paddling to avoid the surging logs, debris and dead cattle. One mistimed stroke would have meant sudden death. With tireless endeavour he continued to pluck one survivor after another from treetops and chimneys and ferry them back to land.

By Saturday morning Gundagai was no more. The only building to survive the flood intact was the flour mill on Morley’s Creek. On Saturday another brave aborigine called Jacky Jacky, joined the rescue bid, in a larger bark canoe which could hold more than one person. He was able to rescue several people at a time.

Yarri and Jacky Jacky continued to rescue those who were still clinging to life in treetops during the night and through the next day Sunday June 27. The epic rescue took three days and two nights of exhausting effort. Yarri had rescued 49 people and Jacky Jacky another 20. History does not record names of all the people rescued or drowned because there were many strangers passing through town. Only about one third of the bodies were recovered. However the number of lives lost was estimated to be between 80 and 100.

Yarri and Jacky Jacky saved 69 people between them. They were motivated to do so out of love for their fellow man in a time of need irrespective of race or colour. They were well aware of the white settler’s suspicions and folly in not heeding the aboriginal warnings. They knew such a disaster was inevitable. The rescues are an important demonstration of the common humanity and goodwill that the Aborigines maintained towards the white settlers in spite of the diseases, depopulation and social disruption they had suffered since the advent of the Europeans.

Many Gundagai descendants owe their very existence today to the bravery of these two great heroes. If the situation had been reversed one can only hope that the white settlers would have risked their own lives to save the aborigines.

For their efforts Yarri and Jacky Jacky were presented with inscribed bronze gorgets (medallions) to be worn around their necks. Both are now exhibited in Gundagai museum. Jacky Jacky’s gorget was lost for many years until it was unearthed by the tyne of a scarifier when a Nangus farmer was preparing a cultivation paddock. In 1990 the gorget awarded to Yarri was handed to the Gundagai Museum by a resident of Cootamundra who found it in an old house in Sutton Street, 25 years earlier.

For the remainder of their lives, Yarri and Jacky Jacky were entitled to demand sixpences and other trifles conducive to Aboriginal comfort from all Gundagai residents – which demands, when in reason, were not refused.

A Hema regional map is the ideal way to find your way around outback NSW.

Although Yarri was well treated by most white people as he got older, he did not get the same respect from everyone, as an article in the Gundagai Times dated 29 June 1879 shows:

‘A gentleman, who passed through South Gundagai on Monday, complains that he saw some individuals whom, he supposes, would expect to be considered men, maltreating and teasing an unfortunate blackfellow, whom he subsequently ascertained was Old Yarri. He reminds us that this blackfellow was instrumental in saving the lives of many white people in the disastrous flood of 1852, and that the only thanks he received was to be kicked around by a lot of white rascals. Through the passing of time we have come to respect the Aboriginal people of this land and we hope for the future that Australia will be as one.’

Jacky Jacky’s actual date of death is not known, however he pre-deceased Yarri. He was buried under an orange tree near the homestead owned by Peter Stuckey at South Gundagai. At that time Jacky Jacky was employed as a station hand on the property. His wife was grief stricken and sat under a tree further up the hill in Eagle Street, where she commenced the death chant. She too died within a few days. Unfortunately, the orange tree and surrounds were demolished by the Department of Main Roads at the time of the highway by-pass in 1976. Jacky Jacky’s burial site is now covered by the Hume Highway near where the present McDonalds Restaurant is situated.

Yarri’s wife, Black Sally, died on a walkabout in March 1873. Yarri died on July 24 1880 and is buried in the Catholic Section of the North Gundagai General Cemetery.

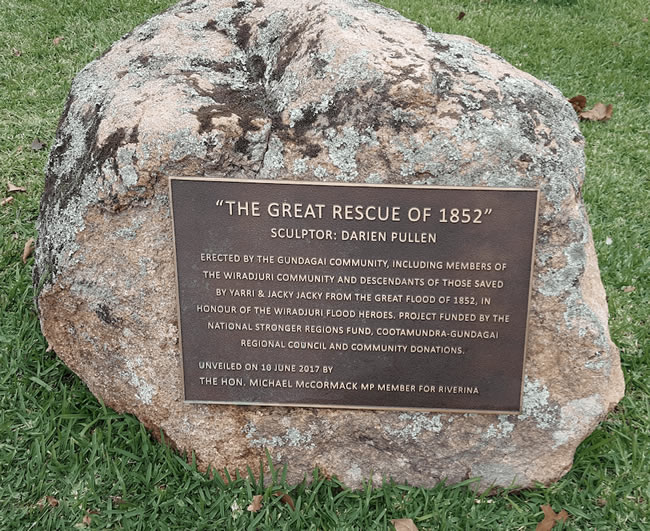

Today there are a number of monuments in Gundagai which honour the memory of Yarri. The flood plain from which he brought so many people to land is now called Yarri Park and the bridge over Morley’s Creek marks the spot where he brought them ashore. Descendants of Fred Horsley who was saved by Yarri erected a sundial in town in his honour and also called one of their rural properties “Yarri”.

Bodie Asimus, NSW

Copyright © 2003 Lateline. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Used by permission, and with thanks.

I just love this fascinating and very human story. People in dire need are rescued by someone whom they had disregarded. Yarri and Jacky Jacky risked their lives over and over again to rescue people from the very floods their people had warned the whites about. This story is a story of compassion and humanity that has touched me. It is also a story of stupendous human effort. To keep going for three days and two nights paddling a bark canoe in a raging torrent is an amazing achievement! Willem

A Hema regional map is the ideal way to find your way around outback NSW.

This page Copyright © ThisisAustralia.au

All the labels you use every day, with excellent service! EveryLabels.com.au

The Go to Guide for 4WDs is an excellent book that gives you great places to explore, and also fit out and maintenance tips for your 4WD.