I suppose one of the purposes of movies is the same as fiction books – to express in a story truths about people and groups of people and the way they think and respond in different situations. To bring to light the things people do that in the immediate action may be hidden by the assumptions of the time. In so doing to challenge the way people think about things. To move people to change their ways of thinking about things that happen

At the same time a movie has the purpose of entertaining people, to give them a good time, and to make them feel good about some part of themselves or ‘their’ people, their country.

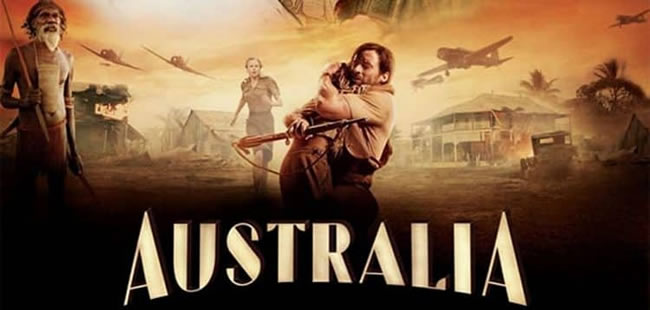

‘Australia’ is a story that touches many aspects of the way we see ourselves. it challenges us, challenges our past, challenges our perception of ourselves. It shows the Australian character in both some very positive ways, and in some very negative ways.

We all like to identify with Drover, the tough, fearless, rugged individual Aussie bushman who is employed by no-one and answers to no-one, able to solve problems, faithful to his friends, willing to walk outside the square by identifying with Aboriginal people when doing that made him an outcast in the white society he came from.

We don’t like to identify with Fletcher, who treated the Aboriginal woman he lived with with contempt and abused her, was betraying his employer by secretly working for the opposition, who murdered his boss twice (not the same boss, but still his boss, if you know what I mean!). Yet we (almost!) grieve with him and for him in his devastation at the loss of his wife.

And we don’t like to identify with the arrogant King Carney, the cattleman who wanted nothing more than a monopoly in the beef industry in the Northern Territory, and would stop at almost nothing to get it. Yet we feel for him when he speaks with Sarah Ashley about how he has not been fortunate in family … his success in business seemingly having come at the cost of a good family life.

We admire the quiet dignity of King George, the Aboriginal grandfather of the boy Nullah, but we hesitate to identify with him. We couldn’t anyway. His culture is too foreign. Yet there is a human-ness about him that attracts us.

Australia large map. Great planning map!

We squirm at the insulting racism displayed by so many of the white folk of that time, and we admire Drover for having the courage to reject it and identify with the Aboriginal people, even marrying an Aboriginal girl. But he still has his own forms of discrimination that mirrors our own. That condescension that gives more credit to Aboriginal culture than it deserves.

The story confronts us with ourselves. We Australians, we love to identify with the outback, with the free rugged individuals who live there, at least in our imagination. But almost none of us lives there. Australia is the most urbanised country in the world! Almost all of us live in towns and cities. The idealised rugged Aussie is not the reality of our lives, and our identification with Drover does not reflect the reality of us.

This film shows us what outback Australians are really like, and in so doing shows us what we are really like. It shows us aspects of our human nature that we often cannot see because it is too close to us in our present. We are not always like Drover. Often we are like Fletcher, mean and vengeful and blaming someone else. Fletcher couldn’t stop doing that even after he lost his wife. He was the one who had organised Sarah Ashley into getting Nullah back from the island, but blamed her for his wife’s death because Sarah had swapped shifts with her to go and collect the boy. Can we claim that we have not sometimes acted in vindictive ways just as Fletcher did?

I liked the way the movie showed people from the different cultures caring for each other. The Drover caring for the Aboriginal people, and for a starched and prissy English aristocrat; King George caring for his people, and particularly his daughter, and keeping watch over them, Nullah caring first for Drover and then also for Sarah Ashley. The prospect of a genuine reconciliation between the Aboriginal people and the western society that is thrust on them seems real – a possibility that is reinforced at the end of the film by the statements about government policy on assimilation changing and about the apology given by the government earlier in 2008.

But there is a danger here. A danger that we’ll feel good about these things and return to our comfortable lives and do nothing more about it. But the plight of the Aboriginal people is worse now than it was then. Whole Aboriginal communities are effectively sidelined from participation in Australian society. The Collins Report on Aboriginal education in the Northern Territory 1999 found that some 5000 Aboriginal children in the Northern Territory had no access to a secondary school! Drug and alcohol abuse are an unfortunate feature of a significant number of Aboriginal communities. Pornography and the accompanying sexual abuse of women and children is a significant problem. Added to this is a horrendous suicide rate.

This problem has become much worse since the departure of the missions some 35 – 40 years ago. This generation has been referred to as the ‘lost generation’ Adding to the suffering of the ‘stolen generation’ so graphically pictured in the movie, there is now the lost generation.

Australia must not forget its Aboriginal people. We must care for them, care enough to act. Care enough to not over romanticise their culture. But care enough to take the action that will make their future far more positive than it is now. But that’s for another post!

Stories are meant to confront us with the reality of ourselves. Australia has done that, and done it in an entertaining way. The entertainment is great. The scenery spectacular. The silence of the outback is sharply contrasted with the noise of the pounding of thousands of hooves; the sharp crack of a rifle. You can almost feel the heat, the flies, the sweat. It challenges and it lifts you. I loved it!

Its not the perfect movie. Some have said its too long, but I didn’t notice. Some have said that its filled with Australian cliches. Andrew Bolt in the Herald-Sun complains that it is not historically accurate, and so he misses the point. It is not meant to be a documentary. It is meant to depict a myth, an Australian myth that is built on but is not identical to history. As Kim Mahood in her intriguing book about life in the Australian outback, craft for a Dry Lake, shows, myth and reality are sometimes hard to separate. Myth is meant to explore some aspect of the human experience and in so doing be a mirror for all of us.

If you haven’t seen it, its definitely worth the watch!

Willem

This page Copyright © ThisisAustralia.au

All the labels you use every day, with excellent service! EveryLabels.com.au

Australia large map. Great planning map!